Richard Hugo’s Triggering Town changed my life. Before I read it, I was a short Vietnamese woman with a lisp. OK, perhaps I exaggerated. Still, if you’re even remotely interested in creative writing, you owe it to yourself to read it. Were I emperor, I’d make it law that no author could receive a rejection without a copy of Triggering Town, and also a year’s supply of bacon. Perhaps this is why I am not emperor… I read Triggering Town as part of my MFA curriculum, and oddly enough there was a point of realization: the one piece of advice Hugo wrote which stuck with me the longest was a comment on teachers. Teachers teach how to write like them, they’re essentially implying the student should embody what they are. That’s not necessarily a bad thing – Liz Strout taught at Queens and I’d give popular parts of my anatomy to write half as well as she does. Still, the impact of an MFA program on a writer’s style cannot be overstated. After graduation, it was a year before I had anything published. During that time, I was writing an enormous amount of bad fiction. Luckily my MFA taught me to recognize my own inadequacies. I had to un-learn some of what I was taught.

This advice made me realize something I’d been fomenting over as a reader for Carve. An awful lot of MFA student fiction sounds the same. The tone is the same, usually dismally emotionally  repressed with flowery prose. I’ve gotten so that I can spot a currently enrolled MFA student most of the time (let’s face it, there are exceptions to every rule). When I decided to write this topic up, I went through a few drafts that read just as bad as the fiction I was bashing. I think what it comes down to is a matter of teaching. Most fiction writers are taught to write what we know, a mantra codified in nearly every fiction class since the first stories were scrawled on cave walls with bat guano. If writers only wrote what they knew, the world would be filled with crappy stories about breakups and parking tickets. Granted, some really fantastic stories are written by authors who’ve had amazing life experiences, but for the majority of mortals, daily excitement is limited to the Barista spelling our name right when they scrawl on the coffee cup. I think the lesson should be: write what the limit of your imagination compels you to see. Otherwise it puts a whole new spin on Fight Club, and I’d like to think Chuck Palahniuk is not batshit crazy.

repressed with flowery prose. I’ve gotten so that I can spot a currently enrolled MFA student most of the time (let’s face it, there are exceptions to every rule). When I decided to write this topic up, I went through a few drafts that read just as bad as the fiction I was bashing. I think what it comes down to is a matter of teaching. Most fiction writers are taught to write what we know, a mantra codified in nearly every fiction class since the first stories were scrawled on cave walls with bat guano. If writers only wrote what they knew, the world would be filled with crappy stories about breakups and parking tickets. Granted, some really fantastic stories are written by authors who’ve had amazing life experiences, but for the majority of mortals, daily excitement is limited to the Barista spelling our name right when they scrawl on the coffee cup. I think the lesson should be: write what the limit of your imagination compels you to see. Otherwise it puts a whole new spin on Fight Club, and I’d like to think Chuck Palahniuk is not batshit crazy.

MFA fiction often reads like an over-produced song sounds. The story strikes very specific beats, usually with an overly dramatic opening in mid-conversation. I’ve often rallied against this, and I’ll say it again: I’m likely to reject any story that starts with a conversation because I think it does a disservice to the reader. Sure, there are examples where it’s worked, but there are far more examples where it doesn’t. You start mid-conversation, and you have to immediately back up and fill the reader in to what’s going on. Don’t do that.

MFA fiction themes tend to be centered around relationships, death, death and relationships, student problems, or some utterly bizarre and outlandish concept that no modern reader has been born who could possibly appreciate your story. These kind of stories can still work, but they need to be fresh and they almost never are. Think of the deluge of vampire fiction – nobody wants to read about sexy vampires anymore, and the re-imagined dark prince has also been done to death. Your bad breakup story, or your best friend killed story, they’ve also been done to death. If you’re going to write about an emotionally heavy topic, remember the simplest thing: the reader has no stake in your characters and won’t care unless you make them care. Your teary-eyed re-telling how your best friend was clipped by a train when you were eight is likely not going to be the celebrated fiction you think it is. I’m sorry you had such a traumatic childhood, but you really do need to distance yourself from the story before you can write about it well enough to make a reader want to stick with you. Most emotional stories simply don’t earn their ending, doubly so if it’s an abrupt ending. Take the time to make the reader care. If you’ve ever read Stephen King’s earlier works, they’re good stories because he makes us care about the characters before anything terrible happens to them.

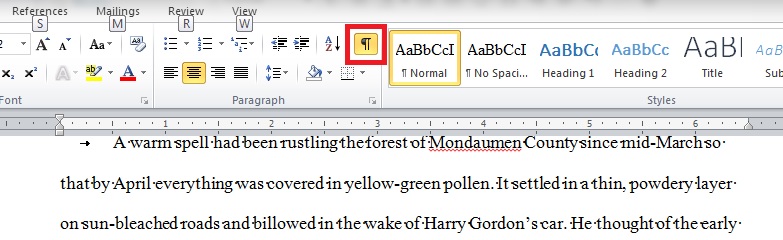

MFA fiction tends to over-weigh prose with back story. I’m a huge advocate for back story, but mostly for the writer’s sake. If you know every detail about your character from their favorite ice-cream to the reason they hate watching reality TV, you’re doing something right. If you include all those details in your story, you’re missing the point. Detailed characters and plots are set dressing to the story. If you know your character is manic about getting a job, you don’t need to tell the reader. Write manic into your story and the context will be enough. Pair down your prose and cut the back story to a few well-placed lines. I honestly think this is a trend in modern times. Some of my favorite stories from the mid-nineteenth century were terribly overwritten. Modern readers will rarely stick with a story that lingers too long.

And lastly, I leave you with this tidbit: as a writer, the best advice we can give other writers is honesty. If your writer buddy reads your work and levies nothing but praise, they’re probably going to hit you up for a loan in the near future because nobody’s draft work is that good. If I critique a story for a stranger or a friend, I’m apt to tell you exactly how I feel – often how bad it is. I’ll also tell you what I think works, but it’s the broken parts we dwell on. As a writer, you can’t fixate on bad criticism. If your aunt Gertrude simply says your story sucks, you need to ask yourself why. If a reader’s reaction is honest, it can never be wrong.

I’ve often commented that Fifty Shades of Grey’s success stemmed from the simple fact that e-readers were prevalent and the time was right for anonymously reading sultry fiction. I certainly can’t count it as riveting literature in the same category as Lolita, though I’m sure author E.L. James has less concerns over literary merit than sales. Fifty Shades serves as an ideal tale of marketing, right-place-right-time, and tenacity.

I’ve often commented that Fifty Shades of Grey’s success stemmed from the simple fact that e-readers were prevalent and the time was right for anonymously reading sultry fiction. I certainly can’t count it as riveting literature in the same category as Lolita, though I’m sure author E.L. James has less concerns over literary merit than sales. Fifty Shades serves as an ideal tale of marketing, right-place-right-time, and tenacity.